On this page

- Governance arrangements across the disability supports ecosystem have been evolving

- Current national governance and funding arrangements for disability have not delivered the hoped-for outcomes

- Financial cost sharing, incentives and accountabilities are currently unbalanced

- The voices of people with disability are fragmented in disability policy, planning and implementation processes

- The Panel’s vision: A compact between governments for a comprehensive and unified disability ecosystem

- Recommendation 20: Create a new compact between Australian governments

Governance arrangements across the disability supports ecosystem have been evolving

Over time, governments of Australia have committed to a series of overarching agreements and strategies that aim to create an Australia where people with disability have the same rights, recognition and opportunities as everyone else. The NDIS is only one part of this.

To put into effect Australia’s commitment to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), governments agreed the National Disability Agreement (NDA) in 2008. This aimed to improve the lives of people with disability and set out funding arrangements, roles and responsibilities and priority actions for disability services in Australia.305

In 2010, the first National Disability Strategy (NDS) was developed following the findings of SHUT OUT: The Experience of People with Disabilities and their Families in Australia.306 The report documented the experience of people with disability, including social exclusion, discrimination, lack of services and support, poor employment opportunities and outcomes and a lack of accessibility.307 The NDS “was the first time all levels of government committed to a unified, national approach to improving the lives of people with disability” and addressing societal change.308

The introduction of the NDIS represented a significant investment in Australia meeting its obligations under the UNCRPD. The NDIS is governed under a series of bilateral agreements between the Australian Government and each state and territory which set out roles and responsibilities as well as funding arrangements.309

The successor to the NDS is Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021 – 2031 (ADS). The ADS was agreed by all governments in 2021 with the aim of improving inclusion and progressing attitudinal change. It is underpinned by five Targeted Action Plans, covering employment, community attitudes, early childhood, safety, and emergency management and has explicitly added changing community attitudes as an outcome area.310

These agreements and strategies sit alongside other government agreements. Australia is a signatory to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). UNDRIP affirmed the right of First Nations people to self-determination and participation in decision-making matters that affect their rights, including First Nations people with disability.311

In 2020, all governments and First Nations people, as represented by the Coalition of Peaks, committed to the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. This commits all governments to work in new ways to drive better outcomes across particular socioeconomic outcomes. The agreement is underpinned by priority reforms including strengthening the community-controlled disability sector. Disability is also identified as a cross-cutting outcome area that needs progress to mitigate the compounding effects of intersectional inequality.312

Back to topCurrent national governance and funding arrangements for disability have not delivered the hoped-for outcomes

The promise of these commitments to people with disability remains a work in progress. People with disability continue to experience discrimination and poorer outcomes on a range of key measures including health, education, employment, and social connection.313

- Health: Those with profound or severe disability are almost nine times as likely as adults without disability and almost twice as likely with adults with other disability to assess their health as fair or poor.314

- Education: Of people aged 15 to 64 with disability acquired before the age of 15, more than one in five left school before aged 16 compared with one in 11 of their peers without disability.315

- Employment: People with disability experience lower labour market participation rates than their peers - 53.4 per cent compared to 84.1 per cent.316

- Social connection: People with disability aged 15 to 64 are twice as likely (17 per cent) to experience social isolation as those without disability (8.7 per cent). This is consistent across all age groups, the largest gap being between people aged 15 to 24 with disability (18 per cent) and those of the same age without disability (6.6 per cent).317

In addition, rates of disability for First Nations people are higher than the general population.

- One in five (72,700) First Nations children aged under 18 have disability, compared with one in 12 children in the general population.

- Approximately 35 per cent (274,400) of First Nations people under 65 years of age have disability, three times higher than the general population.318

- Around 202,200 First Nations adults between 18 and 64 have disability representing 45 per cent of all First Nations adults. This increases to 79 per cent or nearly four out of five First Nations adults aged over 65.319

Despite this reality, and the commitments under the UNDRIP and the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, First Nation issues are not appropriately prioritised through current disability governance arrangements.

For First Nations people with disability, this represents a critical gap in a commitment by all Australian governments under the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Not enough has been done to identify, develop or strengthen independent accountability mechanisms that work with government to identify and eliminate racism, embed and practice meaningful cultural safety, monitor progress, listen and respond to concerns about mainstream institutions and agencies, and report publicly on transformation.320

[First Nations] peoples are more likely to experience disability but are less likely to access support services than other Australians. This demonstrates a fundamental problem with the accessibility of disability support services for [First Nations] peoples.

The separation of governance, strategy and investments in NDIS bilateral agreements and broader disability commitments under the ADS contributes to an unbalanced ecosystem. In 2021-22, 93 per cent of all government funding for disability was directed to the NDIS.322 There are few disability supports outside the NDIS and many mainstream and community services remain unavailable, inaccessible and not inclusive (see Recommendations 1 and 2).

The Productivity Commission reviewed the NDA in 2019 and found it had not had a strong influence on policy, and no longer had a connection with disability support funding that was governed under bilateral agreements between the Australian Government and states and territories.323 In particular, it found the complexity and lack of connection between differing national policy and strategy arrangements had contributed to a failure to deliver a connected system that drives access and inclusion for people with disability.324

While the ADS has only been in operation for a short time, we have identified a number of issues that are likely to limit its effectiveness. We acknowledge all levels of government have committed to deliver more comprehensive reporting through the ADS and significant work has been undertaken in developing an outcomes framework and formal reporting mechanisms. However, many of the activities in current Targeted Action Plans represent narrow jurisdiction-specific programs that were in place prior to the ADS being agreed.

The ADS is also not a multilateral funding agreement between governments with investment directly linked to outcomes. As bilateral NDIS agreements are the sole agreement linking funding and deliverables, parties have focused on meeting their responsibilities within the NDIS at the expense of a thriving foundational support system and accessible and inclusive mainstream services for all people with disability. Other sector specific Federation Funding Agreements do not currently have practical clauses to ensure outcomes are measured and achieved.

Re-organising funding and access to disability supports must support universal access and continuity of services without resulting in further cuts to services. Any inter-governmental agreement underlying it must bind state and territory governments to their commitments.

Financial cost sharing, incentives and accountabilities are currently unbalanced

The NDIS is jointly funded and governed by all Australian governments. State and territory governments make annual fixed scheme financial contributions reflecting their respective population sizes, and adjust their contribution each year by a set escalation rate of 4 per cent to reflect inflation and population changes.326

The Australian Government also provides annual scheme financial contributions. This includes all administration costs and 100 per cent of the costs of those aged 65 and over, in line with broader aged care funding arrangements. The Australian Government also pays all costs associated with higher participant numbers and higher per person care and supports above the agreed capped escalation rate of 4 per cent per annum in state and territory bilateral agreements.

The 2017 Productivity Commission review of NDIS costs identified that funding for the scheme should be sufficient, predictable, and incentivise effectiveness and efficiency.327 It also noted the need for Commonwealth-state collaboration and accountability and the importance of a connected system

Ideally, the NDIS would operate as part of a seamless system of mainstream and disability services that takes a lifetime, insurance-based approach. That is, early interventions and well-targeted preventative care would occur in a coordinated way to minimise the overall costs of mainstream and disability services, and maximise the wellbeing of participants in those systems...Gaps in the NDIS can impose costs on mainstream services, and vice versa.

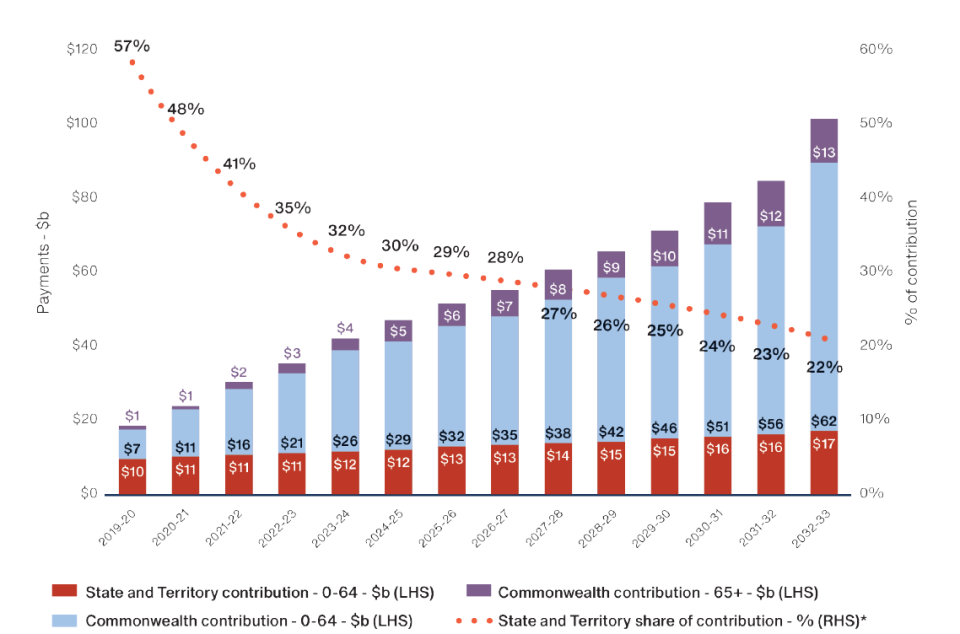

As at 30 June 2023, the NDIS supports over 610,000 participants, at a cost of $35 billion in 2022-23, with further forecast growth to $92 billion in 2032-33.329 This has seen the Australian Government’s share rise to 59 per cent in 2021-22, while state and territory government contributions have fallen to a combined 41 per cent.330

Under current settings, in 2032-33 the Australian Government’s share will rise further to 78 per cent, while the state and territory contribution will fall to just 22 per cent (see Figure 16).

* Projected State and Territory share of contribution is based on a 4% growth rate from 2021-22 ROGS

The financial arrangements for the NDIS were designed to recognise states and territories do not have the same access to growth revenues as the Australian Government. However, a fixed rate of increase for states and territories means there is no direct financial incentive to support policy and governance responsibilities to improve scheme sustainability.

Governments have taken a first step to help moderate cost-growth with the NDIS Financial Sustainability Framework agreed by National Cabinet in April 2023. This provides an annual growth target in total costs of the NDIS of no more than 8 per cent by 1 July 2026 with further moderation of growth as it matures.331

Current arrangements reduce the urgency for all governments to work collaboratively around shared responsibilities for NDIS participant outcomes and to improve the effectiveness of the entire disability supports ecosystem. There can also be perverse incentives for all governments to underinvest in foundational disability supports and mainstream services outside of the NDIS.

States, schools or other services should not be blamed for following the incentives created by the NDIS. From the perspective of the State or Territory this behaviour is highly responsible: it maximises the resources coming into the State; benefits people with disabilities within the State or Territory; while reducing the pressure on the State’s own tax payers.

Given the developments of the last ten years, we believe there is a need to align financial incentives, accountabilities and cost sharing arrangements between governments to ensure better outcomes for all Australians with disability.

To create a joined-up ecosystem of support NDS agrees that a whole of government approach is needed… History suggests that an agreement of some sort that will hold governments publicly and fiscally accountable will be required to ensure that these services are available to support people with disability.

A powerful mechanism for ensuring governments deliver on commitments is independent monitoring and public reporting. Reporting on outcomes for both the ADS and the NDIS are provided to Disability Reform Ministers. Neither approach involves independent review nor are there consequences for non-performance

While work is underway to develop the National Disability Data Asset, there is also limited access to data at present. This means there continue to be gaps in the evidence available about outcomes related to inclusion and access for people with disability.

Back to topThe voices of people with disability are fragmented in disability policy, planning and implementation processes

People with disability are involved in planning and implementation of disability supports as members of the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) Board, the NDIA’s Independent Advisory Council (IAC), and Australia’s Disability Strategy Council. However, none of these bodies has a remit across the entire disability supports ecosystem. These structures mirror the existing segregation of responsibilities for the NDIS, foundational and mainstream supports.

This approach contributes to an arbitrary divide between people with disability who have access to the NDIS and those that do not. It creates fragmented coverage of issues that affect people with disability, and means no single voice can speak across all the elements of policy that affect the lives of people with disability. This means the voices of people with disability are often diluted and less effective in influencing decision-making.

Particular groups of people with disability experience additional barriers in influencing policy. These include children and young people, those with experiences of intersectional barriers and discrimination, people with intellectual and/or psychosocial disability and/or autism, and those who are non-verbal.334

A substantial percentage of NDIS participants are aged under 18, yet their voices are not represented. At a recent major conference about the NDIS, there was no representation of children and young people, their voices or their unique needs

…section 127 of the NDIS Act should be amended to provide that the NDIA Board must include at least one First Nations person at all times

All levels of government should provide mechanisms to support the involvement of people with intellectual disability on Disability Advisory Committees

While governments have been good at setting up a range of consultative groups to help with design and implementation of policies, we have heard that these groups are too often absent from decision-making and have little influence on major decisions about supports and services.

Back to top