Prior to the NDIS, Commonwealth, state and territory governments were responsible for determining what services were provided, and for how much, under different disability support programs.

People with disability had very little visibility or control over these decisions.[1]

The NDIS was established in part to change this. The aim is to empower participants to engage directly with their chosen provider on what services they receive, and what price they would pay. If done well, this new market-based approach would allow providers to receive signals from participants about what supports they value. Providers would compete and have flexibility to implement innovations that could best meet participants’ needs and preferences.

For many participants, having choice and control over who and what services are delivered has led to better participant outcomes.[2]

There is no doubt that the market-based approach has achieved a transformational change and that innovation has emerged in how services are delivered for many NDIS participants.

… a young person with Down’s Syndrome who used to receive services from specialist disability providers, being picked up by a bus for people with disabilities and taken to activities that might or might not interest them. When given a budget for services, the person learned how to take public transport, to go the cinema and to buy her favourite meal from McDonald’s, which she loved. Best practice was not the achievement of the most efficient allocation of resources within an enterprise, but the meeting of the preferences of the person..

However, the NDIS market is still maturing. Not all participants have been able to exercise choice and control effectively. Some participants are not empowered to negotiate with providers to access supports that meet their needs and preferences.

At the same time, service providers have struggled to be responsive to meet the needs of all participants. Some service providers have also reported concerns around financial viability. The 2022 State of the Disability Sector Report found '… pessimism about the operating conditions facing the non-government disability sector has been increasing for a number of years'[4] – with 36% of organisations expecting to make a loss or deficit in 2022-23, up from 23% in 2021‑22.[5]

The challenges faced by participants and service providers are symptomatic of underlying issues in the current approach to delivering NDIS supports (Figure 1).

Over-reliance on competition as the only market mechanism

Choice and control has been foundational to the design of the NDIS.

The first decade of the NDIS has been characterised by the assumption that pure competition alone could deliver choice in quality services that are fit for individual participant needs and wants. It was also assumed that the market for disability services would function well once mature, providing all participants with a choice of high-quality services. In practice, this has not happened for many participants and supports.

Thin markets – where the number of providers or participants is too small to support the competitive provision of services, or to support any provision at all – have left some participants with limited, or no, access to supports or certain types of supports.

Under the current market-based approach, some participants across Australia are not accessing supports despite having the budget to do so. This is most stark in remote and very remote communities where over one in three mature participants (who have been in the NDIS for over a year) are not accessing daily activity supports, and over one in four are not accessing therapy supports that assist with building skills and independence.

Competition between multiple service providers is not always possible and may not provide participants with real choice in quality supports. There can be high ‘switching costs’ for participants to change providers. Participants may be slow to switch between providers when dissatisfied. In this case, market ‘competition’ will be less effective. Other mechanisms (including reliable, timely and effective information provision, effective navigation and coordination support, and proportionate safeguarding) may be needed to ensure the delivery of safe and quality supports.

The NDIS also needs contestable arrangements to ensure providers are responsive to participants in remote and First Nations communities where the conditions for strong competition are not met. Contestable markets (including one with a single active provider) can help ensure providers are responsive to participants where there is a credible threat of replacement. Contestable can be applied at different levels in the market:

- at the ‘service level’ for a group of participants

- for a ‘bundle’ or ‘wrap around’ supports for an individual or group of participants

- at the ‘whole of market’ level for a community (such as, in remote communities).

Some markets for group supports (such as, transport [6] or community participation) may require governments to help participants pool their funding to meet their collective needs. When done well, delivering supports to meet the needs of the group could also help build the social capital of participants and benefit the broader community.

The focus on competition, however, has not supported a systematic approach to coordinating or ‘pooling’ demand across multiple participants to attract providers who are willing to deliver a service for that market.

If a provider needs to travel a distance, they should try and see other participants in the area too to share the cost.

While the NDIA has recently started to explore ways to pool participant funding through Coordinated Funding Proposals (CFP),[8] much more needs to be done.

The focus on competition also appears to be eroding the collaboration between disability service providers who often need to work together to provide care coordination. The current approach is hindering knowledge sharing and collaborative working.

… in this early stage of NDIS roll out service providers still perceived that the historical collaborative relationships of the past were largely being maintained. However there was also acknowledgement that a competitive environment was emerging and that this was already having some negative impacts on the ways in which information was being shared between organisations and the way staff were able to manage their time. These impacts have the potential to effect care coordination as this has traditionally relied upon integrated services which are able to collaborate and share information on clients.

While a few communities of practice have emerged, they have not been enough to drive quality or innovative service provision.

Back to topA lack of accessible and timely information coupled with unclear navigation and coordination of supports

For NDIS markets to function well, participants need clear and accessible information to act as informed consumers. Information on what supports are available, what these cost, and what good looks like is critical.

NDIS providers also need sufficient information to respond appropriately to what participants need and want. Information is needed for providers to:

- compare and benchmark their service offerings with others’

- learn from each other for ongoing improvement and innovation

- develop an evidence base for what works and what doesn’t work.

Information on what, and how, supports can be delivered and how they are paid for is hard to find and understand

Overwhelming amount of information on website. Not easy to try to understand if you are able to purchase something … there often seems to be conflicting information and I don't want to live in fear of being audited and having to repay or have self-managed revoked which is what some people are claiming.

Currently, most participants and their families are not supported to make decisions as informed consumers.

It is difficult to access and understand information on what supports can be purchased, along with the prices and quality of these supports (Figure 2). Participants and providers are required to make sense of information in individualised NDIS plans alongside navigating complex guidance, policies and rules.

Information on the NDIS and NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission (NDIS Commission) websites is difficult for participants, providers and the general public to navigate, find and understand.[11] This makes it difficult for participants and others to access and compare information about the prices of supports and quality of providers in the market.

Much of the information currently available – through governments and broader sector driven initiatives (such as online forums) – provides little help to participants to determine what services should be delivered, what good services look like, or what they should cost.

Reliable, timely and accessible information is also unlikely to be sufficient, noting that many NDIS participants and their families and carers are time poor. For others, there can be language, educational and cultural barriers so tailored advice and capacity building from trusted independent sources are an essential adjunct to good quality information.

Governments do not have the information to effectively steward markets

The NDIA and NDIS Commission capture limited data on the experiences of participants, workers and providers. This is not systematically shared with the market to generate incentives to compete on price and quality, or to drive innovation.

For both agency-managed and plan-managed supports, transaction data gives some indication of who is getting, and providing, what services. However, little information is captured on how, where and how well services were delivered.

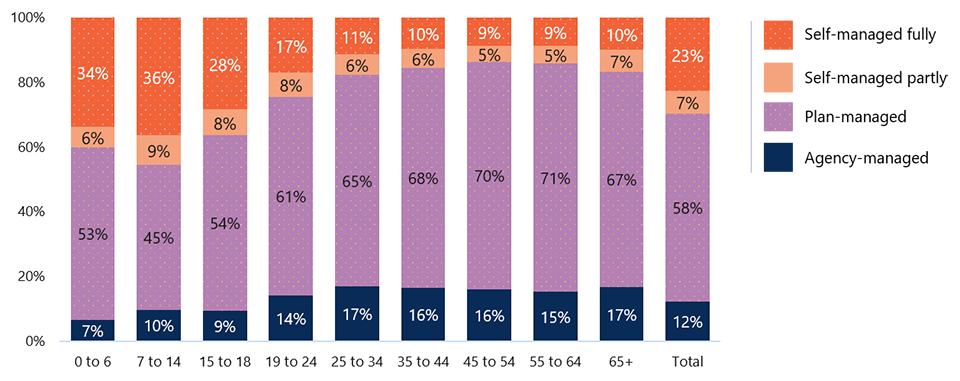

Even less information is captured where participants are self-managing their supports (Figure 3). For the quarter ending 31 December 2022, the market for self-managed supports made up 12% of the NDIS market in terms of payments.[13]

Visibility of different NDIS markets will also vary. For example, information on what supports are being used and what works is not captured for around 40% of participants from aged 0 to 18 years (Figure 3).

Feedback about service providers is typically collected on a complaint basis across different government agencies. This includes through the NDIA, NDIS Commission, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), and state and territory governments. Each can collect different pieces of feedback – for example, the NDIS Commission deals specifically with complaints relating to the compliance of NDIS providers.

Even when collected, feedback is not widely shared across the NDIS market. This makes it near impossible to effectively understand, let alone monitor, how the market is working.

Feedback about service providers is typically collected on a complaint basis across different government agencies. This includes through the NDIA, NDIS Commission, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), and state and territory governments. Each can collect different pieces of feedback – for example, the NDIS Commission deals specifically with complaints relating to the compliance of NDIS providers.

Even when collected, feedback is not widely shared across the NDIS market. This makes it near impossible to effectively understand, let alone monitor, how the market is working.

Altogether, the currently available forecasts of participant demand for NDIS supports[15] and existing NDIS market information[16] are not enough for governments to effectively monitor and intervene in the NDIS market. Currently available information and data is not sufficiently accessible, detailed or frequent enough for governments to identify emerging issues or gaps in the market. It is also not enough to identify whether trends in market dynamics and behaviours are consistent with delivering outcomes for participants and a sustainable scheme.

Currently available tools provide little information for NDIS providers to respond to participants’ needs in an effective and timely manner. So market information asymmetries exist between participants and providers as well as providers and governments.

Participants can find it difficult to navigate the market and find the right providers and supports

Increased transparency of what is happening in the market can help drive better participant and scheme outcomes. But this alone is not enough.

For instance, a carer for an NDIS participant told us that one of the main problems with the scheme is that it is difficult to find providers:

It's a full-time job for someone who is supposed to have a disability. … It's too much. Especially when we want to find the right one for the right price we should be getting. Those providers who provide one solution stop, cost too much for the funding we get. But finding different ones takes too much time to shop around. It is hard for family member who also need to work and earn a living to provide at the same time.

Under current arrangements, some participants may be able to seek help from a local area coordinator (LAC) or a support coordinator to find and connect with funded and mainstream supports. In some instances, their plan manager can also help to find and connect with service providers.[18]

How well this currently works for participants is highly variable.

Huge amount of stress and time experienced when dealing with the NDIS …. Difficulty accessing services because LACs won’t recommend them, only provide a long list of possible providers when the person with the disability can’t read/contact people.

Some providers have adopted online-based or technology-backed solutions to reduce ‘search costs’ for participants.[20]

Some online platforms help participants find and match with support workers or service providers, while others include forums for participants to share their experiences. Some of these platforms also capture and share information on prices and participant feedback on the quality of services, to allow for easier comparison. How quality and safeguarding arrangements apply to providers (including platform providers) will be explored as part of the broader Review.

Participants need to get the mix of supports that are right for their needs

There is no consistency and I get a different answer every time I ask a different person. Your LACs are not trained properly … The NDIS is so overly complicated that I need to pay a Plan Manager (way too expensive) and a support coordinator (also expensive) to help me navigate.

The biggest challenges for participants are knowing what supports could be purchased and arranging these supports.

Even self-managing participants, or the people who self-manage on their behalf, find this difficult. In early 2022, the two biggest challenges for self-managing participants surveyed were ‘Knowing what can be purchased’ (reported by around four in five participants) and ‘Finding / arranging supports’ (reported by around three in four participants).[22]

Less than half of NDIS participants receive funding for support coordination to help them arrange supports.[23] While not all participants will require support coordination, the basis on which participants are funded for support coordination is unclear.

Funding for plan management may also be included in participants’ budgets if they wish to use a plan manager to help them pay for services and monitor their budgets. Some plan managers have used their visibility over the unregistered providers in the NDIS market to develop platforms (such as Kinora and Hey Hubble) that help participants find and connect with suitable service providers.

However, there is confusion about the roles and responsibilities of different market intermediaries in helping participants navigate the NDIS and access supports.[24] This is further exacerbating participant confusion about how their NDIS funding can be used.

… LACs do not seem to have the time, inclination or skill to support people to build capacity to understand their NDIS plans, the scheme, how to work with providers (safeguarding). It is not unusual for a participant or nominee without support coordination funding to come to me for plan management services halfway through their plan, having not engaged with anyone, because they have no idea what to do, or where to go, and have not received any support from the LAC or ECEI coordinator.

Some participants, providers and other stakeholders have also raised concerns around the potential conflict of interests for support coordinators[26] and, to a lesser extent, plan managers. This includes concerns about ‘provider capture’ which may increase participants’ vulnerability to potential harm, abuse, neglect or exploitation.[27] Other participants value the choice and benefit of being able to choose a single provider who can deliver their supports.

Back to topPoor market design means that incentives for providers are not aligned to participants’ and governments’ interests

When well-designed, market-based approaches for social services – where participants have choice and providers compete – can foster innovation, lower the cost of service delivery, and improve the quality of supports and participant outcomes. Realising the benefits of a market-based approach, however, requires that the scheme settings align incentives for participants, providers and government. The implementation of the NDIS market has not seen these incentives align to support a well-functioning market.

As the NDIS is fully government-funded, it does not operate as a private market

Markets for social services that are largely funded by governments (including the NDIS) are best described as ‘social markets’ or ‘quasi-markets’. In a social market, service providers often include not-for-profit and government providers. Choice of provider may be exercised on behalf of the consumer, and/or the size of the market is determined in part or fully by the size of government funding.

In the NDIS, participants purchase supports using their allocated NDIS budgets. This means that participants may be less sensitive to prices than if they were purchasing supports using other sources of funding, such as personal income. At the same time, prices of supports are critical for service providers, and affect providers’ willingness and ability to supply supports.

Participants may seek increases to their budgets if they run out of funds. This can be encouraged by provider behaviour, which has the potential to increase plan costs without a substantial change in participant need nor an improvement in participant outcomes. Participants do not receive any benefits from ‘saving’ funds in their budget. There actually may be concerns from some participants if they do not spend their funds, they may risk future cuts to their budget. Participants have told us they are afraid that their budget will be cut in the future if they don’t spend the full amount of their current budget, even if they do not need it. This is therefore creating a perverse incentive.

Providers have little incentive to compete on price or quality

Price caps act as an ‘anchor’ but mostly do not adjust for quality or complexity. As such, providers have little incentive to charge below the price cap.

Providers also have little incentive to innovate and consider quality beyond the minimum requirements in the NDIS Quality and Safeguarding Framework, or the standards set through professional and registration bodies – such as, the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) for therapy providers.

It has also been suggested that providers are not sufficiently incentivised to invest in the quality of their workforce. Some providers noted challenges with investing in training when workers can leave their organisations to set up as independent contractors or join online platforms.

Registration is the only consistent measure of quality and provider performance that participants can use when selecting their providers. However, the correlation between quality and registration is not clear. Some participants have suggested to us that their non-registered providers are their highest quality, most innovative and best value for-money supports.

Participants cannot easily compare services or negotiate prices without easily accessible, complete and accurate information. Providers have limited incentives and incomplete information to foster competition on price or quality of services. The lack of accessible and comparable information on provider performance works against competition and makes it difficult for participants to purchase on quality and price.

The large reliance on fee-for-service payments can get in the way of delivering ‘value-based’ supports

Inherent friction exists between the fee-for-service payment approach and the investment principles of the scheme. The fee-for-service payment approach rewards higher levels of activity, usually support hours. This approach encourages short-term transactional relationships in service delivery rather than rewarding providers for investing in the capability of participants to reduce their ongoing needs for formal supports.

Providers may also act to increase demand for their supports, even when these do not represent value for money or improve participant outcomes. This incentive for providers is exacerbated in the NDIS, as participants’ budgets are fully government-funded. This may also be compounded in cases where participants rely on the professional opinions of their providers about the level of servicing that is beneficial.

Providers, therefore, have a financial incentive to increase the volume of supports delivered and recommend additional supports that may not be essential to participant outcomes.

Back to top